By: Shashank Shenoy

Agriculture has always been touted as the backbone of the Indian economy and rural India as its lifeblood. Rural life has always been looked at from a gaze of naivety- as a life that is laidback, free of worries and simple. Peeling back the layers of idealised rural life, and replacing the rose-tinted lens with a magnifying glass, exposes the unsettling signs of distress. Therefore, the primary aim of this article is to emphasise the importance of rural issues in the upcoming general elections and urge readers to take into account the rural perspective when casting their votes. This is crucial because rural issues have far-reaching effects that resonate beyond just rural areas, impacting even the affluent and urban populace. Later in this article, we will delve into the reasons behind this interconnectedness.

With 60% of India residing in rural areas - they have the potential to hurt the incumbent government. However, in recent times the ruling party seems to be immune to the growing rural distress in India. During the NDA-I regime’s final 3 years, a period marked by sluggish agricultural growth at 2.8% and widespread drought affecting almost 40% of the nation, the GDP deflator for agriculture registered negative figures for the first time in many years. This indicated a concerning trend of diminishing earnings for farmers[1]. Consequently, the BJP faced electoral setbacks in three pivotal states—Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Rajasthan—which raised concerns about their prospects in the forthcoming general elections in 2019. The outcome, however, defied prevailing belief. In 2023, The BJP won with an even bigger majority and even succeeded in winning back the states that they had lost.

Does that mean the distress in rural areas has vanished and they have now moved into the Amrit Kaal? The data doesn’t seem to suggest so. One factor that may contribute to the apparent lack of impact on electoral outcomes could be the BJP's successful implementation of strategic community mobilisation among rural voters.

Let us first understand what the word that has been sprinkled over this article very liberally- “Rural Distress”- even encompasses. Rural distress refers to the economic, social, and sometimes environmental challenges rural communities face. Several indicators show that these challenges are real for our rural citizens.

Employment

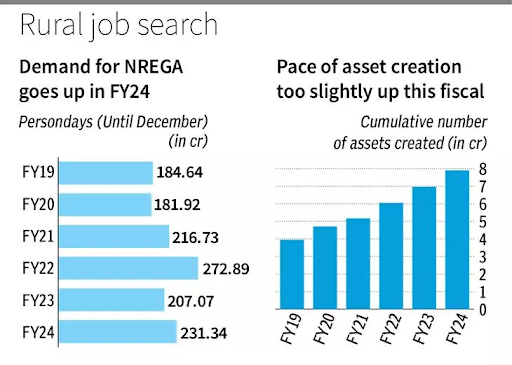

To begin with, unemployment always has and continues to plague rural India. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) has seen an 11% per cent increase in employment generation in the last quarter of FY 24[2]. Demand for jobs under the scheme this year has surpassed the demand in FY 21- which saw the Covid 19-induced lockdowns and subsequent reverse migrations to the countryside. This is a worrying trend because the MGNREGA is often the “employment option of last resort”. There is a large gap between market wages and the wages offered in MGNREGA. MGNREGA wages in most states are only ⅔ of the market wages- and in some states, they are even lesser. Therefore, more demand for these jobs shows that fewer people have other job opportunities.

Moreover, if we look into these numbers a little bit- between 2017-18 and 20020-21- there were 82 million jobs generated in the rural economy[3]. While that sounds like great news at face value, close to 60% of these jobs were due to an influx of women and close to 50% were in agriculture.[4] Even in the MGNREGA, women comprised 57.8% of the scheme beneficiaries in 2022-23 — a 10-year high.

“The share of female labour in the total labour force increased from 23.1 to 29.5 per cent between 2017-18 and 2020-21. The increase in female labour force was found much higher than the increase in male labour force in all the years of PLFS data. Between rural and urban areas, female labour force showed much higher percent increase in rural areas”

-Changes in Labour force and Employment in

Rural and Urban India: 2017-18 to 2020-21

While we associate an increase in women's participation in the workforce as a positive trend, this data suggests that much of the rise in female participation is in low-quality, self-employed roles, especially in rural areas. This often translates to lower wages, job insecurity, and limited opportunities for skill development or career advancement. Moreover, a significant influx of the workforce into agriculture is generally a sign that other industries like manufacturing and services aren’t doing well. At the moment, PLFS data shows us that about 37.5% of women workers are unpaid, which has increased by 32% since 2011-12 and 2017-18. Further, only about 13% of the women in the workforce are getting paid.

This is further evidenced by a significant rise in self-employment between 2017 and 2022, particularly driven by unpaid family workers. This trend indicates a shift towards more precarious forms of employment. Additionally, the increase in unpaid family work among female workers suggests a decline in the quality of employment opportunities available to them.[5]

Income and Consumption

This section has been notoriously difficult to research- because of the lack of data released by the government and recent, publicly available surveys on incomes and consumption in India's vast rural hinterland.

Income is a very important metric through which we can evaluate the standard of living of our citizens. Even more important than unemployment is the quality of employment and wages, as we discussed earlier. This is purely because the poor do not have the luxury of being unemployed.

Farm output which holds a 15% share in our economy- is projected to grow at a sluggish rate of 1.8% this financial year as compared to 4% in the previous financial year according to the most recent NSO estimates. With agriculture being the key sector in the rural economy, income and multiplier effects can create ripples, impacting other sectors of the economy. The primary reason for this was the erratic rain patterns and low reservoir levels in a majority of the states in India.

In the chart below, one can see the continuous decline in the rural wages for both agricultural and non-agricultural workers. In the last five years of NDA-2 (2019-20 to 2023-24), the annual growth rate of real rural wages (wages that have been adjusted for inflation) has become negative for both agriculture (-0.6 per cent) and non-agricultural jobs (-1.4 per cent). Furthermore, real rural wages experienced a continuous decline for 16 consecutive months up to the latest available data in March 2023.

Data related to income from agriculture also demonstrated a concerning picture of rural India. Here is a table that quickly helps one understand the dependency of rural households on agriculture.

Category | Percentage of Rural Households |

Agricultural households (produce > Rs. 4,000 as per NSS) | 54% |

Farming as principal source of income | 38.80% |

Agricultural households with ≥50% income from farming | 31% |

Rural households entirely dependent on farming | 21% |

Source: Situation Assessment of Agricultural Households and Land and Livestock Holdings of Households in Rural India, 2019.

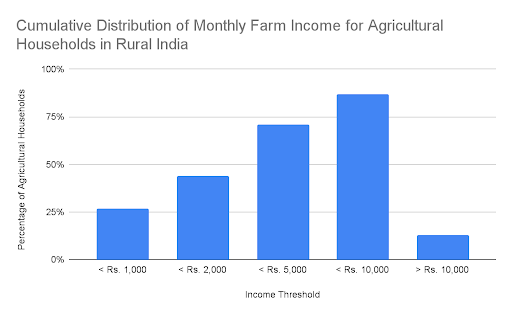

Using the latest data from the National Sample Survey’s “Situation Assessment of Agricultural Households” from 2019[6][7]- which offers insight into the monthly earnings of farming households in rural India, we can try to understand how households that depend on agriculture are earning. Unfortunately, the findings depict a shocking reality. According to the survey- which defines an agricultural household as one receiving produce worth more than Rs. 4,000 from agricultural activities and having at least one member who is self-employed in agriculture in the last 365 days- the national average stands at Rs. 5,298 for monthly farm income. While that is an incredibly low amount to begin with, dwelling deeper into the numbers shows that there is a substantial amount of disparity in agricultural income as well. In the table below, we can see that merely 13% of the agricultural households earn more than Rs. 10,000 a month from farm income. Moreover, a shocking 71% and 44% of the households earn less than Rs. 5000 and Rs. 2000 respectively from farm income. In all, 72% of agricultural households earn less than the average amount from farming.

The survey also pointed out that non-farm income tends to increase the total monthly income for these families. Even after accounting for non-farm income, it revealed that 68% of agricultural households earned less than Rs. 10,000 a month.

While these are national statistics, there is even more disparity between different states. In Jharkhand, Odisha, West Bengal, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Madhya Pradesh, the majority of agricultural households, ranging from 75% to 90%, earn less than Rs. 10,000 per month in total income- even after taking into account non-agricultural income.

These concerning indicators aren't just numbers on a page; they represent tangible hardships for a significant segment of our society. The combination of soaring inflation and dwindling real wages means that many rural families are being forced to make sacrifices, even in meeting their most basic needs like food. While there haven’t been studies conducted with a large sample size to study how consumption has been impacted, nor has the government released any consumption-based data recently, Reuters conducted a survey of 50 households in rural areas of states including Uttar Pradesh, Odisha, and West Bengal. Out of all the households surveyed, 75% said they had cut down on milk; 56% had cut down on proteins like dals, meat and eggs; and 50% said they had reduced consumption of edible oils. Further, they estimate that rural spending fell by 0.5% in the July- September 2023 period[8]. One may argue that drawing conclusions for a sample size that small is statistically unsound. Nonetheless, these anecdotal findings shed light on the tangible consequences of economic strain on rural families and it offers a glimpse into the challenges many households are going through.

Another interesting trend economists have been using to predict and understand the health of rural economies is the sale of tractors. Tractors have seen a steep decline in key states in the west and south in the first 9 months of this fiscal year, dragging overall sales down by 4%. Even the rural FMCG growth trajectory witnessed a notable downturn, with sales declining by 7.5% in November, accentuating the persistent weakness in rural demand. This decline, coupled with a significant slump of 9.6% in rural growth, reflects the ongoing challenges faced by FMCG companies in penetrating and sustaining market share in rural areas. Despite sporadic upticks in October driven by festive stocking, the overall trend underscores the enduring struggle to stimulate consumption and drive growth in rural FMCG segments.[9]

Lost Lives- Suicides in Rural Distress

Under the pressure of stagnating wages, low quality of employment, rising prices and rising indebtedness, farm-related suicides have been on the rise. The distress in the agricultural sector is evident as 11,290 farmers and agricultural labourers- unfortunately ended their lives last year. In fact, suicides in the farm sector have risen continuously since 2020- as can be seen in the graph below- sourced from the recent National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) report.

It is worth noting that, while the number of farmer suicides has gone down over the years, the number of suicides amongst agricultural labourers in the farm sector has shot up. This is a concerning trend as, over the years, an increasing number of agricultural households have been shifting towards farm labor and away traditional agriculture [10]. This shift can be attributed to factors such as land fragmentation, decreasing profitability in farming, and limited access to resources. As a result, the proportion of income derived from agriculture within households is dwindling, while the portion from wages/salaries earned through agricultural-related labor is rising.

Conclusion

Before one closes this article, fearing another onslaught of numbers, let's hit the brakes. But before doing so, let's pose a question that has probably been lingering at the back of one's mind. Why should we care? After all, the time spent pouring over data and crafting this article would be utterly pointless without addressing this fundamental question.

Far from our privileged lives, these problems are real. To begin with, the well-being of our rural communities is directly linked to the well-being of other sections of society. They are the breadbaskets of our country and home to most of our population. Any form of distress in rural areas can have ripple effects on urban life and the economy. Continuously ignoring these communities and their issues can exacerbate and induce social tensions. Addressing these issues, however, can help alleviate these tensions and make them beneficiaries of India’s growth story- “Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas” in its truest sense. Therefore, it's no mere coincidence that this article is being published amidst the backdrop of the farmers' protests currently unfolding around the national capital.

Furthermore, due to climate change, which is- 'a problem created by the rich and borne by the poor’- erratic rain patterns and natural disasters are projected to become more common and severe. Unfortunately, it is the rural communities that will bear the brunt of these man-made disasters. It is, therefore, the need of the hour, that we ask our governments to conceive and enforce plans to mitigate these adverse effects to make our rural economy resilient to the wraths of Mother Nature.

There is an urgent need to move away from myopic policies; involve members of the rural community in debates and discussions surrounding their problems- including tribals, farmers, and oppressed groups; and build a resilient rural economy.

References

Iyer, A. (2018, December 3). Agrarian crisis clear & present danger for Indian economy | Mint. Mint. https://www.livemint.com/Money/qTyGharLfpnjuKbQ7SID0I/Agrarian-crisis-clear--present-danger-for-Indian-economy.html

Benu, B. P. (2024, January 1). Demand for NREGA jobs up, TN sees the highest demand. BusinessLine. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/data-stories/data-focus/demand-for-nrega-jobs-up-tn-sees-the-highest-demand/article67694937.ece

Rural distress: MGNREGA, PLFS numbers spell trouble | Policy Circle. (2022, October 10). Policy Circle. https://www.policycircle.org/economy/rural-distress-mgnrega-plfs/

Rural distress: MGNREGA, PLFS numbers spell trouble | Policy Circle. (2022, October 10). Policy Circle. https://www.policycircle.org/economy/rural-distress-mgnrega-plfs/

Ghatak, M., Jha, M., & Singh, J. (2024, February 2). Quantity vs Quality: Long-term Trends in Job Creation in the Indian Labour Market. The India Forum. https://www.theindiaforum.in/economy/quantity-vs-quality-long-term-trends-job-creation-indian-labour-market

Situation Assessment of Agricultural Households and Land and Livestock Holdings of Households in Rural India, 2019 https://mospi.gov.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/Report_587m_0.pdf

Shukla, V. (2024, February 16). How Much do Agricultural Households Earn from Farming? The India Forum. https://www.theindiaforum.in/forum/how-much-do-agricultural-households-earn-farming

Ahmed, Sharma, & Dash. (2024, January 31). Insight: World-beating growth? Not for India’s rural majority. Reuters. Retrieved March 28, 2024, from https://www.reuters.com/world/india/world-beating-growth-not-indias-rural-majority-2024-01-31/

Dsouza, S. (2024, January 4). FMCG cos to witness low topline growth in Q3, volume growth to remain soft. www.business-standard.com. https://www.business-standard.com/industry/news/fmcg-cos-to-witness-low-topline-growth-in-q3-volume-growth-to-remain-soft-124010301075_1.html

Sangwan, S. S. (2023, October 2). The average Indian farmer is turning more of a laborer today- Situation assessment surveys of agricultural hou. Times of India Blog. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/issues-from-the-ground-and-experience/the-average-indian-farmer-is-turning-more-of-a-laborer-today-situation-assessment-surveys-of-agricultural-households/

Comments